Muhammad Rabnawaz, an associate professor in Michigan State University’s School of Packaging and recent inductee into the National Academy of Inventors, has always believed that the most brilliant solution is also the simplest.

That belief is reflected in his team’s new publication in the journal Advanced Sustainable Systems.

Rabnawaz and his colleagues showed that sodium chloride—table salt—can outperform much more expensive materials being explored to help recycle plastics.

“This is really exciting,” Rabnawaz said. “We need simple, low-cost solutions to take on a big problem like plastics recycling.”

Although plastics have historically been marketed as recyclable, the reality is that nearly 90% of plastic waste in the United States ends up in landfills, in incinerators or as pollution in the environment.

One of the reasons plastics have become so disposable is that the materials recovered from recycling aren’t valuable enough to spend the money and resources required to get them.

According to the team’s projections, table salt could flip the economics and drastically reduce costs when it comes to a recycling process known as pyrolysis, which works through a combination of heat and chemistry.

Although Rabnawaz expected salt to have an impact because of how well it conducts heat, he was still surprised by how well it worked. It outperformed expensive catalysts—chemicals designed to spur reactions along—and he believes his team has just started tapping into its potential.

Furthermore, the work is already getting attention from big names in industry, he said.

In fact, the research was partially supported by Conagra Brands, a consumer packaged goods company. A catalyst worth its salt

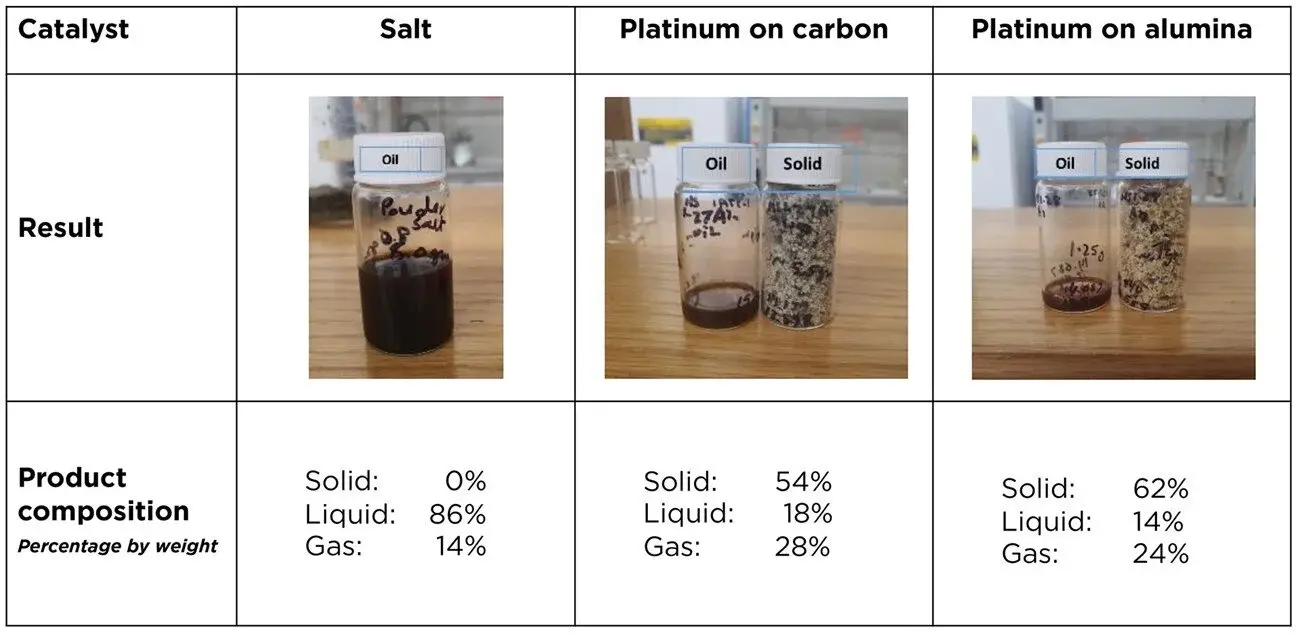

Pyrolysis is a process that breaks down the plastics into a mixture of simpler, carbon-based compounds, which come out in three forms: gas, liquid oil and solid wax.

That wax component is often undesirable, Rabnawaz said, yet it can account for more than half of products, by weight, of current pyrolysis methods. That’s even when using catalysts, which are helpful, but they often can be toxic or prohibitively expensive to be applied in managing waste plastics.

Platinum, for example, has very attractive catalytic properties, which is why it’s used in catalytic converters to reduce harmful emissions from cars. But it’s also very pricey, which is why thieves steal catalytic converters.

Although bandits are unlikely to rob platinum-based materials from a sweltering pyrolysis reactor, attempting to recycle plastics with those catalysts would still require a hefty investment—millions, if not hundreds of millions, of dollars, Rabnawaz said. And current catalysts aren’t efficient enough to justify that cost.

“No company in the world has that kind of cash to burn,” Rabnawaz said.

In earlier work, Rabnawaz and his team showed that copper oxide and table salt worked as catalysts to break down a plastic known as polystyrene. Now, they’ve shown table salt alone can eliminate the wax byproduct in the pyrolysis of polyolefins—polymers that account for 60% of plastic waste.

“That first paper was important, but I didn’t get excited until we worked with polyolefins,” Rabnawaz said. “Polyolefins are huge, and we just outperformed expensive catalysts.”

Joining Rabnawaz on this project were Christopher Saffron, an associate professor in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, visiting scholar Mohamed Shaker and MSU doctoral student Vikash Kumar.

When using table salt as a catalyst to pyrolyze polyolefins, the team produced mostly liquid oil containing hydrocarbon molecules similar to what’s found in diesel fuel, Rabnawaz said. Another perk of the salt catalyst, the researchers showed, is it can be reused.

“You can recover salt by simply washing the obtained oil with water,” Rabnawaz said.

The researchers also showed that table salt aided in the pyrolysis of metallized plastic films, which are commonly used in food packaging, like potato chip bags, which isn’t currently recycled.

Although pure table salt didn’t outperform a platinum-alumina catalyst the team also tested with metallized films, the results were similar, and the salt is a fraction of the cost.

Rabnawaz, however, stressed that metallized films, while useful, are inherently problematic. He envisions a world where such films are no longer needed, which is why his team is also working to replace them with more sustainable materials.

Making landfill mining profitable needs to happen for capitalists to want to do it so I guess this is good for now

Immediate red flag to me, when one of the sponsors of the research is someone who directly benefits from its findings. Just like the “sugar doesn’t cause health problems” sponsored by Coca-Cola

I get the skepticism, but where’s the profit in using NaCl as a catalyst in pyrolysis? If anything they’d be pushing a new and exotic catalyst that they can own a patent on.

I hope this is as successful in the field as it is in the lab. We have a massive global plastic problem and anything that can help is needed.

A packaging company investing in recycling research actually seems like quite a good sign to me. We’ve been trying to find ways to tie the responsibility for waste to packaging manufacturers for a long time.

Yeah, but this one will be easy to replicate, and I don’t really expect MSU staff to do open obvious fraud, although it’s not impossible.

If I can get my hands on the paper I have half a mind to try it myself. It’s bonfire season anyway.

Immediate red flag to me, when one of the sponsors of the research is someone who directly benefits from its findings.

Literally the most common reason anything ever has received funding, it doesn’t mean it’s wrong. They don’t really benefit unless it actually works in this case, unlike a sugary drink manufacturer looking to show that sugar is healthy on paper. This is too technical to be helpful to them optically rather it’s helpful in that it actually reduces the impact of their products on the environment in a provable way if implemented allowing them to avoid tighter regulation or outright bans of them. (for better or worse)

That or their motives are less self serving, which is rare in the corporate world but does happen. Sometimes enough people at a company care to make things better.

Also I’m sure they’d love to be able to take those plastics and turn them back into feedstock hydrocarbons to get nice virgin plastic on the cheap as oil prices inevitably rise in the coming decades.

I also get the skepticism, but a lot of research is funded by industry proponents. Usually it’s through the lens of a question they want answered or a gap in the industry. You see this a lot in agriculture and environmental fields.

Does adding an amendment to the soil improve the speed of reclamation at our site? Does this method of handling our tailings yeild a cost savings?

Thank kind of thing

when one of the sponsors of the research is someone who directly benefits from its findings.

That’s basically all of them

Wow, that actually has the DNA of something that could be huge. I can’t wait for replication.

Yes! Reading this article made me feel a little hopeful for the future. Let’s see what comes of it